STRAITS OF FLORIDA – At 2 a.m., oceanographer Ryan Smith was headed into his 12th hour of work with little sleep when trouble started.

From the rear deck of the University of Miami’s research boat, he guided the vessel’s winch to lower a cage containing 14 long, gray tubes, collectively weighing about 1,000 pounds, hundreds of meters deep into the Atlantic Ocean, to record the temperature, salinity and density of the water. But after running smoothly for the first two-thirds of the trip, the sensors now suddenly stopped transmitting data.

There was no time for a hiccup. With urgency mounting, Smith signaled to bring the cage to the surface.

At sea, there is no helpline to call for a broken instrument at this hour (or any hour). If the team couldn’t fix it, they would need to make a 12-hour slog back to Miami through the fast-moving Florida Current – the precise subject they were trying to measure.

For 43 years, scientists have been studying the strength of the water flow between Florida and the Bahamas to learn what drives its changes over time. The information could help scientists answer a pressing question: Is the Florida Current, one of the world’s fastest ocean currents, slowing down? If so, it could indicate weakening of the larger circulation system in the Atlantic Ocean – what scientists call the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) – which could be disastrous.

Even Hollywood has imagined the harm that could result from a collapse of this system of currents, which acts like a conveyor belt as it transports water, nutrients and heat through the Atlantic.

While scientists doubt the scenario sketched out in the 2004 movie “The Day After Tomorrow,” in which the AMOC’s failure prompts a calamitous Ice Age across the Northern Hemisphere, researchers say rain patterns could change or fail in Southeast Asia and parts of Africa, disease may spread to new populations, and temperatures would probably drop across Western Europe. Iceland has even declared that the risk of such a collapse is a national security threat.

But climate scientists are at odds over how soon, or whether, the circulation system may weaken. Researchers largely agree that the AMOC may weaken over this century as the world warms, but they differ on whether the system is already slowing down.

Direct observations of the AMOC’s and the Florida Current’s flow, velocity, temperature and salinity could help clarify this. The Florida Current, which helps shuttle water north, is a key component in calculating the system’s strength.

Traveling between Miami and the Bahamas, a crew from the University of Miami and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration homed in on the Florida Current, the world’s longest nearly continuously observed ocean current. Over 36 sleep-deprived hours, six researchers and seven crew members traversed the ocean, dove underwater and collected gigabytes of measurements. These expeditions gather data that generations of scientists can use to better understand the state of our oceans – and humanity’s future.

– – –

The AMOC debate

For more than four decades, scientists have almost continuously measured water flow across the Florida Current, largely with the help of a decommissioned AT&T telecommunications cable running from West Palm Beach to Grand Bahama Island.

The telephone line wasn’t intended for ocean research, but NOAA scientists noted that it picked up tiny voltages induced by seawater flowing across the Florida Straits, which changed depending on the current’s flow. Using direct measurements of the waterway from research cruises, scientists can convert the voltages into the volume of water carried each second through the strait.

In 2005, British oceanographer Harry Bryden tapped these cable measurements and the limited available ship measurements in a seminal paper that suggested a possible slowdown in the AMOC between 1957 and 2004. Using data across the Atlantic Basin today, scientists have found that the AMOC varies, daily and seasonally, yet it also appears to have experienced a slight weakening over the past two decades.

But is it on a long-term decline because of human-induced planetary warming? Debatable.

The Florida Current is one of the main forces that make up the western boundary of the AMOC. The warm Florida waters feed into the mighty Gulf Stream, which merges with the warm North Atlantic Current headed toward Europe. As the current reaches the Arctic, air temperatures cool the water, which becomes denser. The water sinks and moves south toward the equator, where it is again warmed by the sun and returns north.

“The role of the AMOC in the climate is it carries a huge amount of heat from the equator towards the poles,” said Denis Volkov, who is a co-principal investigator of NOAA’s Western Boundary Time Series project along with Smith.

But scientists say a warming world is throwing off this balance. As Arctic ice melts, freshwater enters the North Atlantic – making the ocean water less dense, so it is less likely to sink. As a result, scientists propose that it cannot power the ocean conveyor belt as well, so less salty, warm water is getting transported northward.

A major shift in the Atlantic Ocean’s circulation could create severe drought in some areas and damaging floods in others. Sea level could rise by a foot or more along the U.S. East Coast if it collapsed.

Scientists have typically used data that indirectly hints at the current’s movement – such as sea surface or air temperature – to reconstruct the oceans in models and track whether the overall system is weakening, but they have reached mixed conclusions.

For instance, a 2018 study plugged sea surface temperatures into computer models to show that the AMOC is weakening. Then, a paper released last January reported no evidence of weakening over the past 60 years after examining data on heat exchanges between the air and the ocean called air-sea fluxes.

Volkov and his colleagues are helping approach the puzzle with observations. In 2024, they reassessed the cable data from the Florida Current, adjusting for changes from Earth’s geomagnetic field. First, they found that the current had remained stable over the past four decades. Then, they updated calculations of the AMOC in this region, which has been monitored for only 20 years or so, with the corrected data and found that the AMOC wasn’t weakening as much as previously calculated at this latitude.

“But there is a caveat that observational data is very short,” said Volkov. He said scientists would need another 20 years of AMOC observations to determine if the small decline is a robust feature and not part of natural variability.

And the AMOC can still weaken even if the Florida Current remains strong, he said, since it is the sum of currents across the basin. But long-term changes in the Florida Current can serve as an indicator of trouble for the rest of the system.

One snag, said Volkov: The serendipitous cable that provided data for more than 40 years malfunctioned in 2023 – perhaps broke. Until it’s fixed, researchers are ramping up their diving operations to recover data from underwater acoustic barometers on the ocean floor.

– – –

The expedition

When the research vessel departed from the university’s dock around 4 a.m. on Sept. 3, the sun and most of the science staff were down for the night. A few shipmates gazed at the illuminated cityscapes from the stern deck, next to the diesel engine’s deep rumble. After traversing rocking waves, the crew reached scenic Bahamian waters eight hours later.

The green F.G. Walton Smith, 96 feet long, and its crew make this overnight trip about six times a year, traveling 93 nautical miles diagonally from Miami toward the Little Bahama Bank. From there, they go west and collect data at nine sites from the boat and dive underwater at two others.

The team’s goal is to determine the amount of water flowing north through the Florida Current per second through a series of underwater instruments, from the boat and from satellites. They also collect temperature, salinity, density and velocity data; velocity and temperature, for example, can be combined to calculate the amount of heat transported across an area.

At the first dive site, a remora – a long, torpedo-shaped suckerfish – circled the two scuba divers less than a mile from the boat. The slender fish is known for a unique fin on its head that suctions itself to sharks, whales and turtles to feed off their detritus. And for a quick moment, it latched onto Leah Chomiak’s head. And her thigh.

Chomiak focused on the barometer in front of her. Her bulky gloves made it harder to use a screwdriver 50 feet below the Bahamian surface. She and her fellow diver held onto the long tubes that had been recording data every five minutes for the previous two months, since the last time divers brought the instruments to the surface and downloaded the data.

“Now we decided to service them more frequently, because, at the moment, this is the only source of data for our Florida Current transport estimates,” Volkov said. The scientists can use the pressure data to help calculate the amount of water flowing through the area.

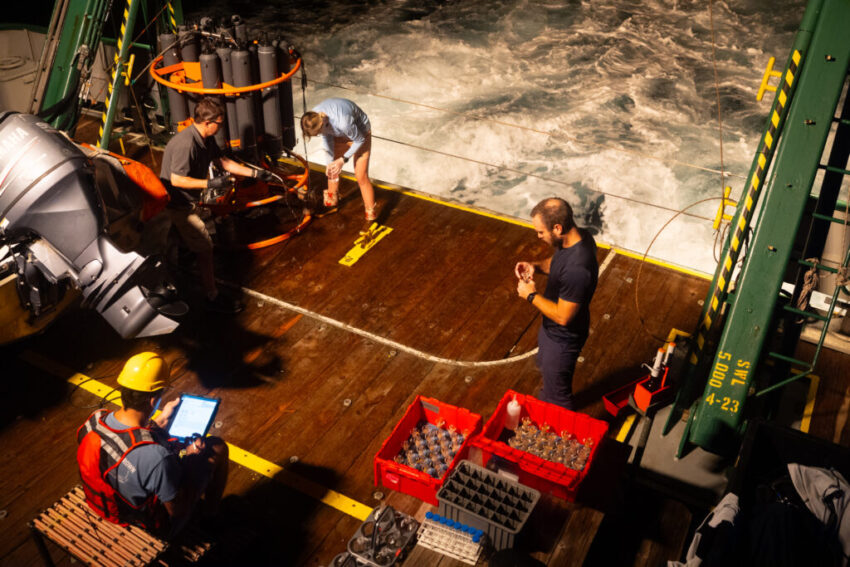

Next, the ship arrived at the first of nine hydrographic stations and lowered a cage of sensors known as a CTD-rosette sampler (CTD stands for conductivity, temperature and depth, although it measures many more properties). Researchers can use the temperature and salt concentrations of a particular mass of water to infer where it came from and how it reaches other parts of the world.

Jay Hooper, who has been on these trips for 10 years and helps with data management, sat at the ship’s computer station.

“Ready whenever you are,” he said into his headset.

From the top deck, the captain lowered the rosette into the water, dropping 60 meters each minute. As the instruments approached the bottom at 486 meters, Hooper said to slow down.

Lines of various colors – representing salinity, temperature and density – squiggled down on Hooper’s computer screen as the sensors dropped. Temperature decreased and density increased as the instruments descended. Seventeen minutes later, the rosette was brought back onto the boat.

After hours of gathering data, Hooper and Smith hit a snag at the seventh station. The rosette now wasn’t sending any information to the computer. Was it human error? Did the instrument break?

The two tried different solutions as the other scientists slept. Then they replaced the sensors’ cable, and as they lowered the rosette, data filled the computer screen.

The boat stopped for the last dive near the Florida coast to retrieve the second set of underwater acoustic barometers. But the water was so cloudy, thick and green that the divers couldn’t see their hands, so they decided they would try on the next trip.

For the next 12 hours, the boat fought against the Florida Current to take the crew home. Some aboard mustered up energy to sing “Happy Birthday” to one of the crew members.

The next morning, Smith and his colleagues processed the data to upload to NOAA’s Atlantic Oceanographic & Meteorological Laboratory website. There were no notes about a cable malfunction, encounters with remoras or sleep deprivation.

The Excel spreadsheet had a single note for each station it recorded: “Profile looks good; use these data.”

Kasha Patel is deputy weather editor at The Washington Post. Based in Washington D.C., she is a stand-up comedian and writer who focuses her jokes on her life as an Indian-American and science.