I’ve been drinking bottled water but now I’m worried about microplastics. What’s the best choice here for my health?

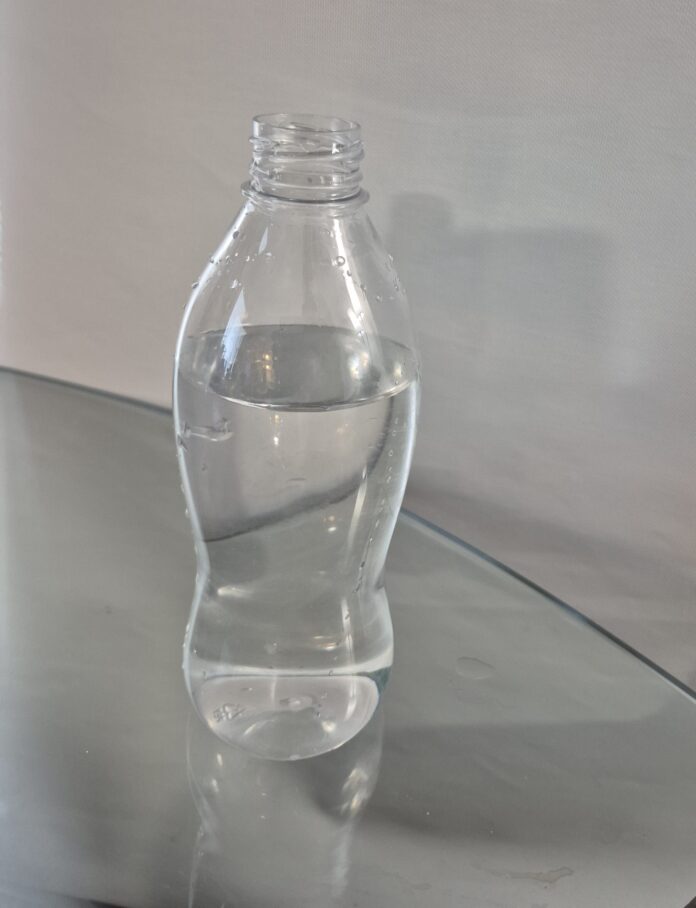

Bottled water often feels like a “healthier” choice – but there’s a problem, particularly if it’s the only type of water you drink: plastic.

Last year, stunned by the mounting data on how often microplastics accumulate in the body, I stopped heating my food in plastic. Frozen microwavable vegetables? Now I steam them on my stovetop. Plastic food containers? Gone – replaced by a set of glass ones instead.

But there was one other big source of plastic exposure I had thought less about: plastic water bottles. While bottled water may reduce exposure to some contaminants, it may increase intake of microplastics.

Microplastics are so widespread that the average American adult consumes or inhales in the ballpark of 100,000 particles annually – and heat is one of the most potent triggers of microplastic shedding.

Experts estimate that people who drink only bottled water may be ingesting an additional 90,000 microplastics every year compared to around 4,000 extra particles for people who rely solely on tap water. While the health risks are still being studied, I try to reduce my intake where I can.

That irony is hard to miss: Many people choose bottled water for their health. Forty percent of Americans believe bottled water is safer than tap water, and hope to avoid contaminants like lead or PFAS, or “forever chemicals,” which are present in almost half of the country’s tap water. These concerns are especially important if your house uses private well water, which serve about 13 percent of the United States and isn’t routinely tested or treated for contaminants like municipal water.

Jill Culora, a spokesperson for the International Bottled Water Association, said in an email that “the truth is microplastics are ubiquitous, and bottled water is just one of thousands of food and beverage products (including soft drinks and juices) packaged in plastic.” She said that “conclusions that drinking water is a major route for oral intake of micro- and nanoplastics are not justified based on the current science available. In addition, there are currently no certified testing methods and no scientific consensus on the potential health impacts of micro- and nanoplastics.”

After talking to multiple experts about the data – what’s known and what’s still emerging – it’s clear that no water solution is entirely perfect. Some systems nicely address one problem but aren’t as great at mitigating others.

But the most comprehensive option? If you’re looking for the broadest protection across multiple contaminants, reverse osmosis filtration stands out.

These systems are different from the common activated-carbon pitcher filters many people already own. Reverse osmosis filters force water through a semipermeable membrane and have been shown to successfully filter microplastics, PFAS and over 99 percent of lead. You can get a countertop system or under-the-sink option, depending on space and budget.

The biggest problem is that reverse osmosis filters are also expensive – they cost anywhere from $150-$600 up front. That’s a real barrier for many households. But compared to a year’s worth of individual plastic water bottles or at-home water delivery with plastic jugs, the investment may pay for itself within a year or two while also cutting down on plastic waste.

– – –

The cheaper, low-tech ways to make water healthier

Even if a reverse osmosis filter isn’t an option, there are practical ways to improve water safety without overhauling your life. Husein Almuhtaram, a senior research associate at the University of Toronto, doesn’t think people should sweat the very low amount of microplastics coming from their tap water – and focus their energy elsewhere.

“Water treatment facilities already provide excellent removal of microplastics. They behave like many other suspended solids that are readily removed during filtration,” he said. In a recent study of 10 Canadian water treatment facilities, Almuhtaram’s group found that more than 97.5 percent of microplastics were removed during treatment.

The potential issue with bottled water comes from microplastics that get introduced later from the bottle itself – even if initially that water was well-filtered. “There is a big difference in microplastic concentrations found in tap water, which may contain tens or low hundreds of microplastics per liter, compared to plastic water bottles, which may contain tens to hundreds of thousands of particles per liter,” Almuhtaram said.

So if you’re weighing budget, access and chemical removal, here are a few simpler steps that can still make a meaningful difference:

1. Actually change your pitcher filter. On schedule.

The classic activated-carbon pitcher filters may not perform as well as reverse osmosis at removing PFAS, but they’re better than straight tap water. The pitfall is maintenance.

Heather Stapleton, an environmental chemist and professor at the Nicholas School of the Environment at Duke University, and her team tested 76 different household point-of-use water filters in North Carolina communities to see how effectively they removed PFAS.

Reverse osmosis filters performed the best (removing around 94 percent of PFAS contaminants), but activated-carbon filters still removed a significant portion (73 percent). However, there was a big issue – in some of the activated carbon filters they tested, PFAS levels actually increased after filtration.

The reason? The filters themselves had become saturated with PFAS and were no longer effective.

“It can be difficult to tell when a filter is saturated,” Stapleton said. “So it’s important to change the cartridges as indicated by the manufacturers.”

Who here isn’t guilty of looking at the filter of your pitcher or coffee pod machine and wondering, gee, when was the last time was I changed it?

We’ve all been there. Set a reminder on your calendar.

2. Get your well water tested.

Households that rely on private wells often face different risks than those served by municipal water systems. Unlike city water, private wells are not federally regulated under the Safe Drinking Water Act, which sets a testing cadence, defines limits on contaminants and determines treatments. Studies suggest that compared to children living in houses served private wells can have a 25 percent increased risk of elevated blood lead levels compared with children in homes using regulated city water. In those cases, lead is thought to enter the water supply through corrosion in plumbing and wells. Stapleton advises individuals with private wells to have their water tested by a laboratory with expertise in common drinking water contaminants.

“While there is a cost associated with these tests, it may be worth the peace of mind,” she said.

3. Don’t drink bottled water that’s been sitting in a hot car.

If absolutely nothing else, consider making just this one tiny swap: Don’t drink bottled water that’s been out in a hot car. Remember: heat causes microplastics to leach into the water and it’s a quick way for those tiny particles to multiply.

– – –

What I want my patients to know

When it comes to drinking water, it’s a trade-off. Bottled water can reduce concerns about some contaminants, but it may increase exposure to microplastics. Tap water is inexpensive and often well-regulated, but it can contain PFAS or lead depending on where you live and how it’s treated. Filters such as the kinds I suggest in this column can help, but they vary widely in what they remove, how much they cost and who can access them.

Part of what makes microplastics so unsettling is that the science is still catching up to the routes of exposure and what it means exactly for your health. We’re learning how widespread these particles are and that we’re ingesting them by the gobful, but we don’t yet have precise answers about how much exposure leads to which specific health outcomes.

While the annual estimated amount of microplastics entering our bodies sounds like a lot, Almuhtaram says those values should be viewed with some caution and they may not necessarily be something to worry about.

“We can think of these numbers as the amount that first enters our bodies by ingestion or inhalation, but not necessarily those that will remain,” he said. We have several barriers, including the gut’s defenses, that could prevent them from actually becoming absorbed – resulting in them being simply excreted.

So in situations such as this, I aim for realistic choices that can reduce risk where I can – whether that means filtering your tap water, limiting heat exposure to plastics or rethinking bottled water when alternatives are available.

You don’t need to eliminate every possible plastic from your life to protect your health (neither is that truly feasible). Small, thoughtful changes can still add up over the long term and move you in the right direction.