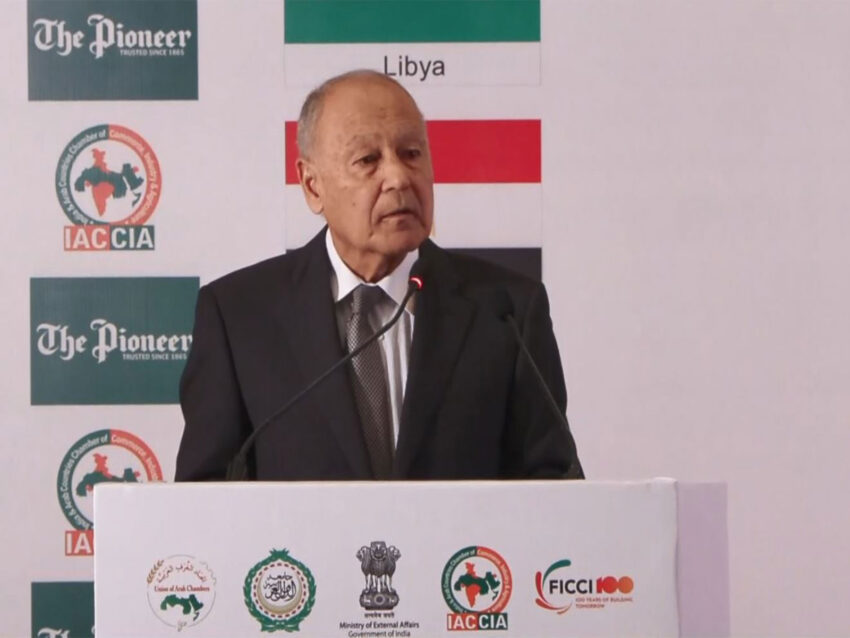

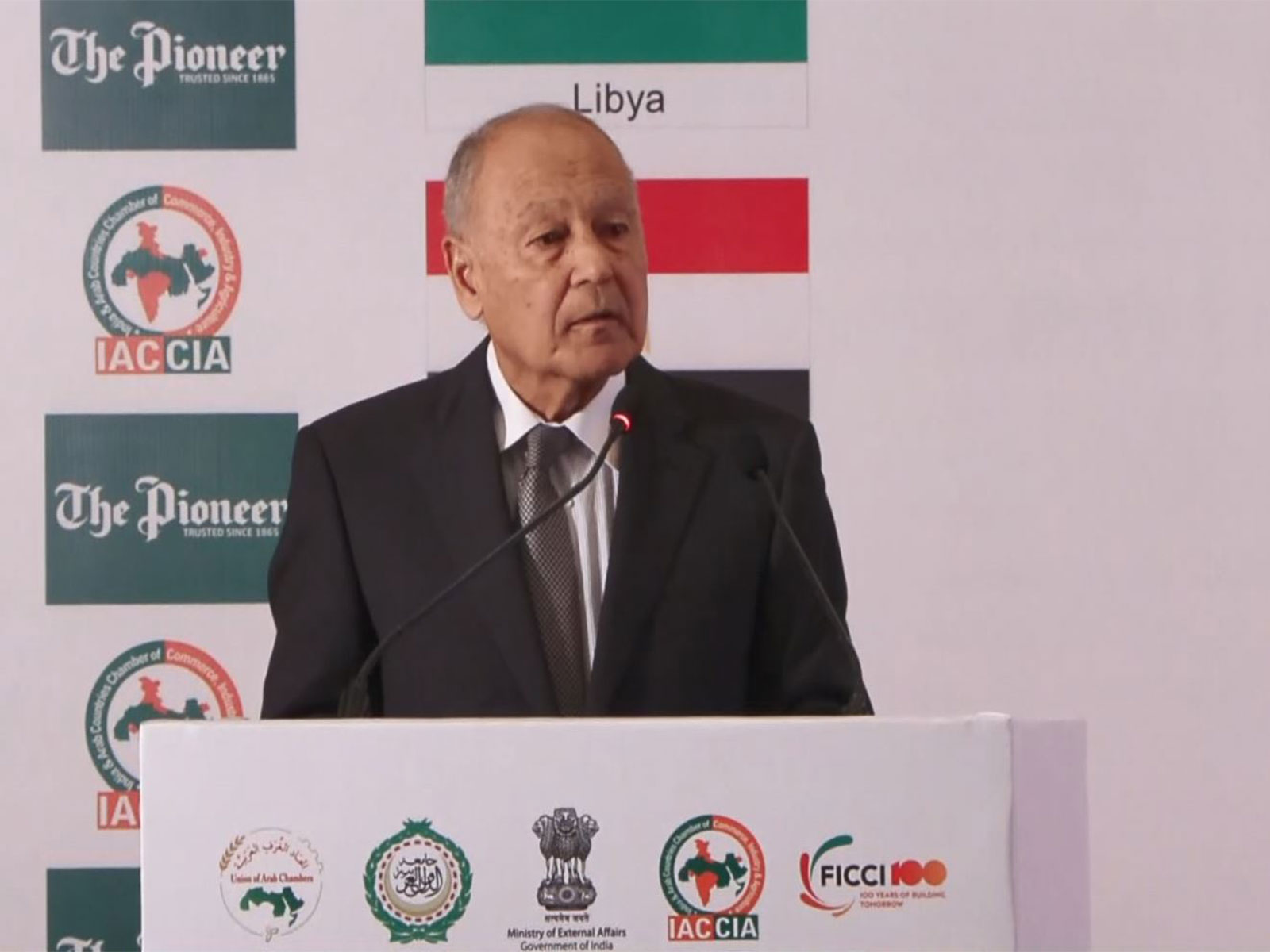

New Delhi [India], January 31 (ANI): Arab League Secretary General Ahmed Aboul Gheit reflected on global power dynamics, saying that major powers avoided nuclear conflict even during the Cold War, while stressing that Russia cannot be defeated in Ukraine.

Setting out his broader view of international stability, Aboul Gheit, speaking on Friday at a public event hosted by the Indian Council of World Affairs and moderated by former diplomat Talmiz Ahmad, said in New Delhi, “In the midst of a Cold War, Russia, the US and China were maintaining peace because otherwise nuclear weapons would have been activated.”

Linking this historical balance to present realities, he added that Moscow continues to strengthen its position, stating, “Russia is building its potential, and no one can defeat Russia in Ukraine.”

Drawing comparisons with earlier conflicts to underline his point, the Arab League chief remarked, “You can defeat Russia in Afghanistan because it is 11,000 miles away from Moscow.”

Turning to current geopolitical realignments, Aboul Gheit also spoke about shifting strategies, saying, “The US is trying to take Russia away from China.”

Referring to earlier developments in Europe to provide historical context, he said, “Russia wanted to join NATO in 1993-94 with the emergence of Putin and the offer of some French politicians.”

That period marked a phase when Russia explored closer engagement with Western security structures, with then-President Boris Yeltsin pursuing a cooperative approach toward the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation, including signalling interest in eventual membership as part of a new European security framework.

During this period, Yeltsin communicated with then-US President Bill Clinton, expressing concern that NATO’s eastward expansion ran counter to the spirit of post-Cold War agreements, even as Moscow initially avoided directly blocking the process and instead viewed engagement mechanisms as a possible alternative to enlargement.

In 1994, NATO launched the “Partnership for Peace”, which Russia joined, with Yeltsin hoping the initiative could serve either as a pathway to membership or a substitute for it, rather than becoming a staging ground for former Warsaw Pact countries to enter the alliance ahead of Moscow.

However, as this programme began facilitating NATO’s expansion, eventually leading to the accession of Poland, Hungary, and the Czech Republic, Russia formally opposed further enlargement in 1995, while continuing to seek a working partnership with the alliance.

Against this backdrop, some European leaders, including former German defence minister Volker Ruhe, argued that Moscow could accept new NATO members if relations were placed on a “fundamentally new, more cooperative basis”, an approach that later contributed to the signing of the NATO-Russia Founding Act in 1997.

Russia’s early interest in integrating with Western security institutions thus stood in sharp contrast to its later confrontational stance, reflecting a brief post-Soviet phase in which Moscow sought accommodation rather than outright opposition to NATO’s expanding role in Europe. (ANI)