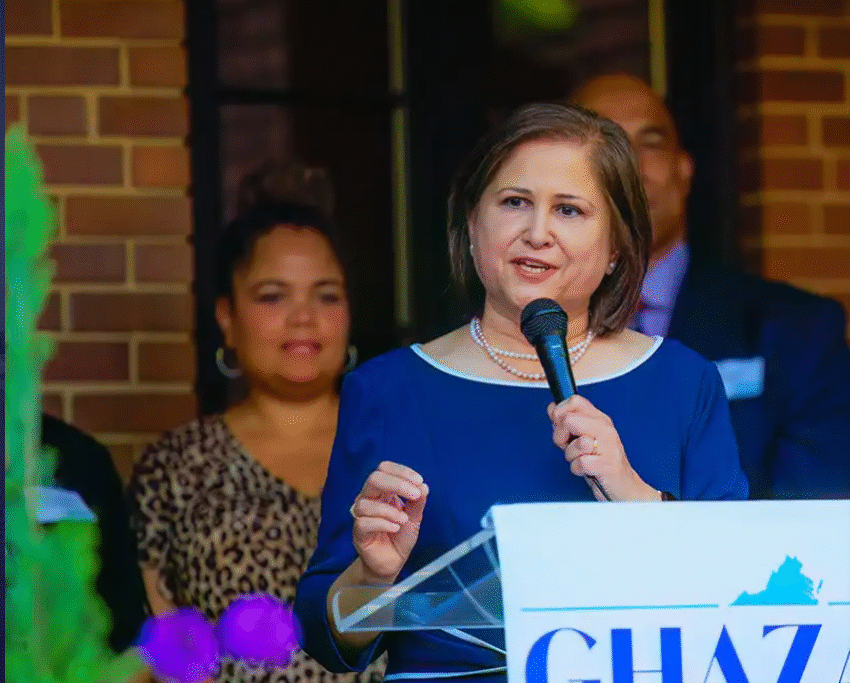

She rarely talks about it at length in public, but Virginia’s new Lt. Gov. Ghazala Hashmi (D) holds a PhD in poetry.

Hashmi, who previously served in the state Senate, has “a tiny little fan base” from her parodies of famous poems crafted during lulls in session that she posted on X. On the campaign trail last fall, she often spoke about the existential angst of Democrats by quoting a lyrical line in Abraham Lincoln’s 1862 message to Congress: “The dogmas of the quiet past are inadequate to the stormy present.”

As she prepared to take office this month, The Washington Post talked to Hashmi about her love of poetry. She shared five poems that have resonated with her as she campaigned during the first year of the Trump administration and, then, became the country’s first Muslim woman elected to statewide office.

She said she turned to these pieces of art as she sought understanding, inspiration or beauty in a rapidly shifting world.

“The truth is sometimes hard, and the truth is ugly,” she said. “But in the truth there’s also the beauty, because once we acknowledge the truth, we have clarity. And we’re able to face ourselves, we’re able to face each other.”

Each poem presents a theme she said has brought comfort, clarity or courage. One speaks to the banality of evil, another to the weight of suffering, a third to listening to your quiet truths, a fourth to facing darkness and finding hope and the fifth speaks to her own past, living in a patriarchal structure and how fathers shape daughters.

As a former English professor at Reynolds Community College and the University of Richmond, Hashmi said each of these are poems she’d teach to explain the current times.

“As much as we have these challenges, it is art that reminds us what it means to be constantly searching for beauty – for grace – in moments of pretty significant pain,” she said. “And that is the critical role that art continues to play. And there is a truth that comes about through art, that forces us to really look and understand ourselves and our communities and our fellow humans.”

– – –

Musée des Beaux

by W.H. Auden

About suffering they were never wrong,

…

– – –

The banality of evil

At a cafe over iced tea recently, Hashmi pulled out a printed version of this 1938 poem. “This one hits me all the time,” she said.

Then she started an hour-long analysis of five pieces of poetry.

“It’s an amazing poem that really captures the banality of evil and the way in which, as human beings, we see tragedy juxtaposed with the ordinariness of life,” she said. “We become immune to the idea of the miraculous or the evil. And maybe that’s because we can’t process it ourselves as human beings a lot times.”

Hashmi points to the stanza about Icarus’ death – people going about their daily lives as a child who can fly also dies going too close to the sun – as a metaphor for these times.

“People keep moving on, and they’re not even aware of the historic significance of the moment that they’re in, or the trauma that somebody else is experiencing,” she said. “The miraculous happens in our ordinary lives, and sometimes we’re just oblivious to it.”

She said that watching the first year of President Donald Trump’s second term brought a “dismantling” of systems, worries about due process and “horrific scenes” as U.S. Immigration and Enforcement officers do their work. She said, on the campaign trail, people brought up their trauma and anxiety.

This poem “helps me make sense of the world in the big picture, that there is a continuity of human existence and our response to the momentous is fairly consistent. … There are some huge seismic shifts that are happening. With our focus on the day-to-day and on the ordinary, we oftentimes don’t have that ability to pull back and have that long perspective, that broader perspective. This is where art really, really helps us.”

– – –

A Sunset

by Robert Hass

…

Here’s another hard right turn. Think

Of how Walt Whitman loved this country,

Loved the President who died. Imagined

Himself as a hand brushing a fly from the brow

Of a sleeping child. In the dark

I thought of a radiant ordinariness

That burned, that burned and burned.

– – –

The weight of suffering

Published in 2024, this poem opens with a reference to the Uvalde school shooting two years before and closes with references to poet Walt Whitman and Abraham Lincoln.

“It’s a painful poem, but it is so resonant with our times,” Hashmi said. “We’re going through such a hugely significant historic moment. And the last time the nation went through something as momentous, I think, is the Civil War.”

She discussed how Lincoln was not just the president, but a metaphor for the crisis the nation faced, and how Whitman portrayed Lincoln as “the epitome and the representation of a nation that’s struggling and suffering, and then trying to emerge out of that darkness.” Hashmi said poetry connects her to broader truths, and reminds her there is a continuity to the human experience.

“I think that is a powerful connection to the past and to the period that we’re going through ourselves,” she said.

“That’s a recurring theme that we see in modern experience, and the immense tragedy is the murder of innocent children and the inability of a society to actually respond in the meaningful way that we need,” she said. “It’s how the ordinariness of that tragedy just becomes a part of our national landscape and our human understanding,” she said.

– – –

The Long Shadow of Lincoln: A Litany

by Carl Sandburg

…

Make your wit a guard and cover.

Sing low, sing high, sing wide.

Let your laughter come free

remembering looking toward peace:

“We must disenthrall ourselves.”

…

– – –

Hope and facing darkness

Sandburg wrote this poem near the end of World War II in conjunction with a painting by the same name by artist Norman Rockwell. Hashmi was drawn to it partly because it opens with the same Lincoln quote she gave on the campaign trail last year, but also for its call to contemplate “the place of our nation within the context of a larger reality.”

Sandburg’s poetry, she says, uses Lincoln’s address “almost as admonition to us as citizens.”

To Hashmi, the line “We must disenthrall ourselves” serves as a reminder: “Don’t be so enchanted with the idea of what we are as a nation that you forget the reality of the struggles that actually create and protect who and what we are,” she said.

She finds the idea repeated throughout the poem.

“It really just hits hard for contemporary audiences,” she said. “People are feeling the tension of where we are as a nation and the fragility of our situation, especially as fundamental rights are being challenged or negated. And our trust in government has been pushed to the extreme.”

Hashmi said she doesn’t believe the country is on the brink of another Civil War, “but we are on the brink of losing our democratic structures. And I think we are in a very dangerous place.”

She reflected that her first three poem recommendations were somber.

“They are also guiding lights toward hope,” she said. “We go through these very, very complex and challenging periods but we do emerge. … Sometimes that’s all we can count on: that we survive, this level of humanity survives.”

– – –

I Have Been a Stranger in a Strange Land

by Rita Dove

…

And there was no voice in her head,

no whispered intelligence lurking

in the leaves-just an ache that grew

until she knew she’d already lost everything

except desire, the red heft of it

warming her outstretched palm.

…

– – –

Listening to your quiet truths

Hashmi said this poem spoke to her about exploring the limits of reason and how accepting truth may come with disruption. She said that sometimes, accessing the truth of a situation is a matter of letting go of the impulse to understand it.

In Hashmi’s reading, Dove’s piece is about how to respond to the world when you can’t make logical sense of it, a skill she’s reached for often during the first year of the Trump administration.

The poem describes Eve in the Garden of Eden “housekeeping in a perfect world” but aware that more must exist outside the gates, even if she can’t describe it. In Hashmi’s analysis, it shows Eve reaching for the apple as embracing her own intuition.

“It was something already within her. The knowledge, it wasn’t the voice of a demon or a serpent tempting her, but something innate that she already knew about the chaos that existed in the universe – the potential for disruption.”

Hashmi said it’s an human impulse to categorize life, but sometimes it’s useless to try to make sense of it.

“We cannot respond to irrationality, and chaos, and disruption, through the norms that we’ve established for ourselves,” she said. “And sometimes it is a matter of letting that go, responding more instinctively.”

– – –

The Death of Socrates

by Jennifer Chang

Like Socrates, my father wants to know what we think and why

So where do I begin?

Yes, the curiosity is genuine, but it is also patriarchal, I suspect. A glass, a mirror,

I am not. Lest we forget,

he is the son of a philosopher, and so I

am offspring to reason’s offspring.

A daughter-loved despite that.

American-loved despite that.

…

– – –

How fathers shape their daughters

Hashmi’s final selection mirrors her own history, written by a poet who, like Hashmi, is an immigrant daughter navigating different worlds and describes the education of a woman growing up around patriarchal values.

Born in Hyderabad, India, while her father studied in the United States for a PhD in International Studies, Hashmi didn’t meet her dad until she was nearly 5.

“We had to build that relationship. I actually remember meeting him. He was a complete stranger,” she said.

He had been raised in a more traditional Muslim culture, she said, but loved his daughters and wanted to see them succeed.

“He had to dismantle some of his own patriarchal assumptions,” she said. “I watched him change and evolve over many, many decades in his own thinking about the role of women and the place of women.”

The poem, she said, describes the challenge daughters can feel, navigating worlds that were not meant for them, building relationships with fathers who think differently.

“That taught me how to think through arguments, how to make effective arguments and how to hold my own position,” she said. “As a daughter, you learn how to do that dance with a patriarchal figure, but that helps you to also define your own identity as a woman.”

Hashmi decided to run for public office after Trump issued a Muslim ban during his first term; her father was angry, “afraid of the ugliness of the political world,” and he tried to talk her out of it. But eventually, she said, he was “tremendously proud.”

He died in 2021, but she thinks he would be proud of her winning and redefining a statewide role shaped by men.

“He saw me break out of certain prisons,” she said. “Many of us who are now in the government spaces, you know, we’re still breaking ceilings that way and defining our own identity.”